Charles Avery Dunning (July 31, 1885 – October 1, 1958) was the third

premier of Saskatchewan

The premier of Saskatchewan is the first minister and head of government for the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The current premier of Saskatchewan is Scott Moe, who was sworn in as premier on February 2, 2018, after winning the 2018 Saskatch ...

. Born in England, he emigrated to Canada at the age of 16. By the age of 36, he was premier. He had a successful career as a farmer, businessman, and politician, both provincially and federally.

A

Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

, Dunning led his government in one general election, in 1925, winning a majority government. He was the third of six Liberal premiers to date. He resigned as Premier in 1926 to enter federal politics and was succeeded by

James Gardiner. He served in the

Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

of

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Li ...

.

After leaving politics, Dunning served for many years as the Chancellor of

Queen's University at Kingston

Queen's University at Kingston, commonly known as Queen's University or simply Queen's, is a public research university in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Queen's holds more than of land throughout Ontario and owns Herstmonceux Castle in East Suss ...

.

Early life

Known throughout his life as "Charlie", Dunning was born in

Croft

Croft may refer to:

Occupations

* Croft (land), a small area of land, often with a crofter's dwelling

* Crofting, small-scale food production

* Bleachfield, an open space used for the bleaching of fabric, also called a croft

Locations In the Uni ...

,

Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire t ...

, England.

[J. William Brennan, "Charles Avery Dunning", ''Canadian Encyclopedia'', 2013.]

/ref> As a teenager, he originally worked in an iron foundry in England, but in 1902, at age 16, he followed a friend's advice and travelled to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

to work as a farm hand.

Penniless when he arrived, within a year Dunning filed for his own homestead

Homestead may refer to:

*Homestead (buildings), a farmhouse and its adjacent outbuildings; by extension, it can mean any small cluster of houses

*Homestead (unit), a unit of measurement equal to 160 acres

*Homestead principle, a legal concept th ...

in the Beaver Dale district, west of Yorkton

Yorkton is a city located in south-eastern Saskatchewan, Canada. It is about 450 kilometres north-west of Winnipeg and 300 kilometres south-east of Saskatoon and is the sixth largest city in the province.

As of 2017 the census population of the ...

.[Heather Persson, "Charles Avery Dunning championed farmers' causes." ''Saskatoon StarPhoenix'', June 25, 2017.]

/ref>[Brett Quiring, "Dunning, Charles Avery (1885-1958)", ''Encyclopedia Saskatchewan''.]

/ref> Satisfied that a permanent move to Canada made sense, he convinced the remainder of his family to come to Saskatchewan, operating a farm in partnership with his father. He eventually married Ada Rowlatt from Saskatchewan, with whom he had two children.[

]

Business career in Saskatchewan

During his career as a farmer, Dunning was involved in the local of the Saskatchewan Grain Growers' Association

The Saskatchewan Grain Growers' Association (SGGA) was a farmer's association that was active in Saskatchewan, Canada in the early 20th century.

It was a successor to the Territorial Grain Growers' Association, and was formed in 1906 after Saskatch ...

, an early proponent of a farmer-owned cooperative grain marketing system. In 1910, he attended the general meeting of the Association. Dunning's enthusiasm was apparent, and he was promptly elected as a director. The following year, he was elected as vice-president of the Association.[Lisa Lynne Dale-Burnett, "Charles Avery Dunning (1885–1958)", in ''Saskatchewan Agriculture: Lives Past and Present'' (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2006), p. 48.]

/ref>

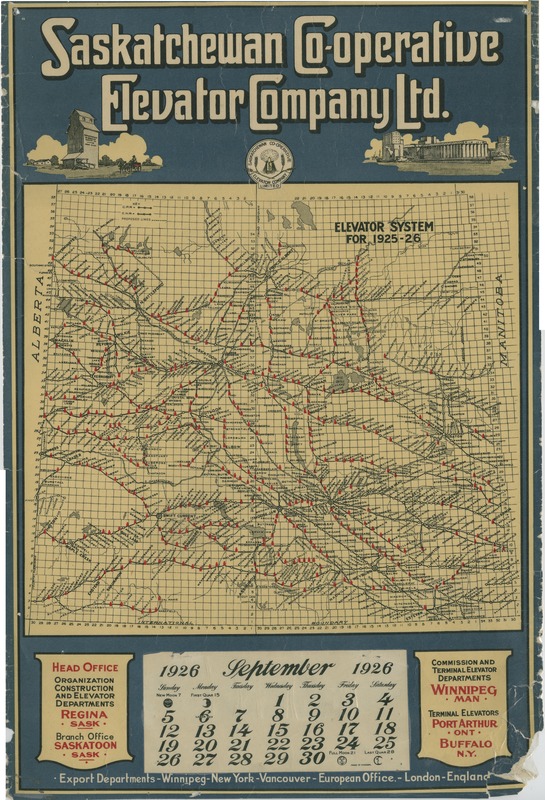

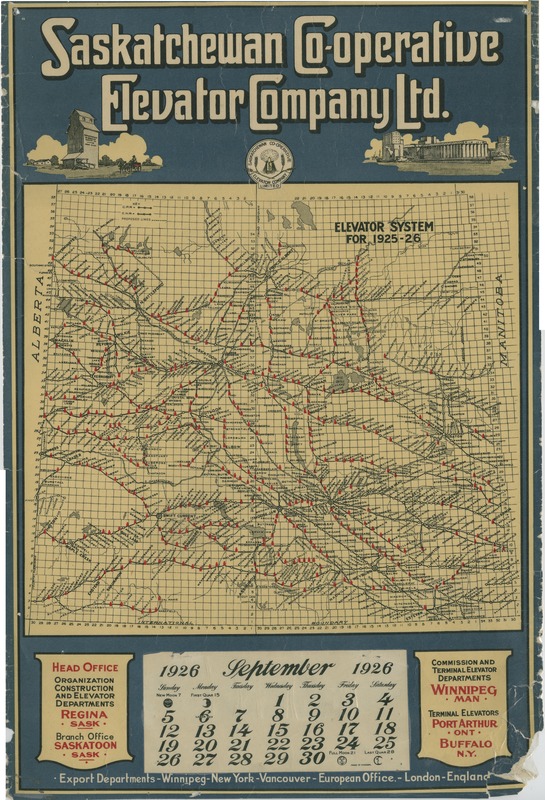

In 1919, Dunning prepared a report on the gain elevator system, which led to the incorporation of the Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company

The Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company (SCEC) was a farmer-owned enterprise that provided grain storage and handling services to farmers in Saskatchewan, Canada between 1911 and 1926, when its assets were purchased by the Saskatchewan Whea ...

by the Saskatchewan government.[ The SCEC was a farmers' cooperative, financed in part by shares purchased by farmers at $7.50 per share, and in part by a loan guarantee from the provincial government.][Brett Fairbairn, "Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company (SCEC)" ''Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan''.]

/ref> A co-operative marketing system required physical assets. Dunning was appointed a provisional director of a board that had only a few months to raise the necessary capital to build a line of rural grain elevator

A grain elevator is a facility designed to stockpile or store grain. In the grain trade, the term "grain elevator" also describes a tower containing a bucket elevator or a pneumatic conveyor, which scoops up grain from a lower level and deposits ...

s. At age 25, the youngest man on the board, Dunning watched as each one of his seniors turned down the critical job of organizing the capital campaign. Dunning took the job and succeeded. The following year, in 1911, he was rewarded for his efforts by being named the first general manager of the company. Four years later, it was the largest grain handling company in the world. Under Dunning's management, the SCEC had built 230 elevators and had handled over 28 million bushels of grains.[

As manager, Dunning was instrumental in developing a provincial hail insurance scheme,][ which survives today as Saskatchewan Municipal Hail Insurance. He also sat on two royal commissions, the Grain Market Commission and the Agricultural Credit Commission.][ He became a wealthy man, with a reputation for integrity.

]

Provincial politics: 1916 – 1926

MLA and Cabinet Minister: 1916 – 1922

Dunning's interests turned to politics. The Liberal government of Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'', ''Rob Roy (n ...

, Saskatchewan's first premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of governm ...

, was tainted with allegations of corruption. Scott resigned, and an outsider to provincial politics, William Melville Martin

William Melville Martin (August 23, 1876 – June 22, 1970) served as the second premier of Saskatchewan from 1916 to 1922. In 1916, although not a member of the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan, Martin was elected leader of the Saskatch ...

, succeeded him as Liberal leader and premier, with a mandate to clean up the government.[Ted Regehr, "Martin, William Melville (1876-1970)", ''The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan''.]

/ref> Martin recruited Dunning to the new Liberal government.[ In October 1916, Martin brought Dunning into Cabinet, appointing him as ]Provincial Treasurer

In Canadian politics the Provincial Treasurer is a senior portfolio in the Executive Council (or cabinet) of provincial governments. The position is the provincial equivalent of the Minister of Finance and is responsible for setting the provinc ...

. Dunning then stood for election to the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan

The Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan is the legislative chamber of the Saskatchewan Legislature in the province of Saskatchewan, Canada. Bills passed by the assembly are given royal assent by the Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan, in the na ...

in a by-election held in the Kinistino constituency in November 1916. Unopposed, he was acclaimed

An acclamation is a form of election that does not use a ballot. It derives from the ancient Roman word ''acclamatio'', a kind of ritual greeting and expression of approval towards imperial officials in certain social contexts.

Voting Voice vot ...

a Member of the Legislative Assembly

A member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) is a representative elected by the voters of a constituency to a legislative assembly. Most often, the term refers to a subnational assembly such as that of a state, province, or territory of a country. S ...

.[Saskatchewan Archives - Election Results by Electoral Division.]

/ref> Dunning held the position of Provincial Treasurer continuously for his ten years as an MLA.[Saskatchewan Archives: Offices Held by Members of the Executive Council.]

/ref>

Traditional politics were being challenged, as farmer movements had become politically active, creating new political parties throughout Canada. Dunning's political astuteness, and his strong background in farmer organisations, were significant factors in the Saskatchewan Liberal Party

The Saskatchewan Liberal Party is a liberal political party in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan.

The party was the provincial affiliate of the Liberal Party of Canada until 2009. It was previously one of the two largest parties in the provin ...

retaining power.[ During his time in provincial politics, Dunning persuaded the farmer's movement in Saskatchewan to support the provincial Liberals, and eventually the federal Liberal party as well, at a time when farmers elsewhere switched their support to the ]Progressive Party of Canada

The Progressive Party of Canada, formally the National Progressive Party, was a federal-level political party in Canada in the 1920s until 1930. It was linked with the provincial United Farmers parties in several provinces, and it spawned the P ...

and the United Farmers.

In the general election of 1917, Dunning won a contested race for the seat of Moose Jaw County Moose Jaw County was a provincial electoral division for the Legislative Assembly of the province of Saskatchewan, Canada. The district was created as "Moose Jaw" before the 1st Saskatchewan general election in 1905. The riding was abolished int ...

by obtaining twice the votes of his opponent. He remained the member for Moose Jaw County for the remainder of his time in provincial politics. Dunning ran unopposed in the general election of 1921, and won a contested race in the general election of 1925 by a 2.5 to 1 margin.

Between 1916 and 1922, Dunning held a series of Cabinet posts. In addition to his ten years as Provincial Treasurer, he also was appointed Provincial Secretary, Minister of Agriculture

An agriculture ministry (also called an) agriculture department, agriculture board, agriculture council, or agriculture agency, or ministry of rural development) is a ministry charged with agriculture. The ministry is often headed by a minister f ...

, Minister of Municipal Affairs, Minister of Railways, and Minister of Telephones.[

]

Premier of Saskatchewan: 1922 – 1926

The continued political tensions between the federal Liberal Party and the farmer-influenced Progressives led to Dunning becoming Premier of Saskatchewan in 1922, at age 36.

The federal Liberals were increasingly unpopular in Saskatchewan, which contributed to the rise of the Progressives. The provincial Liberals continued to advance their position as a farmers' party, to the point that in 1921, Premier Martin severed the organizational ties between the Saskatchewan Liberal Party and the federal Liberal Party.

The federal Liberals were increasingly unpopular in Saskatchewan, which contributed to the rise of the Progressives. The provincial Liberals continued to advance their position as a farmers' party, to the point that in 1921, Premier Martin severed the organizational ties between the Saskatchewan Liberal Party and the federal Liberal Party.[Damian Coneghan, "Progressive Party", ''Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan''.]

/ref> He also recruited another popular farm leader, John Archibald Maharg

John Archibald Maharg (February 2, 1872 – November 23, 1944) was a Saskatchewan politician.

Born in Orangeville, Ontario, Maharg moved west and settled near Moose Jaw in 1890 where he became a grain farmer and cattle breeder. He helped organize ...

. Like Dunning, Maharg had ties to the farmer co-operative movement, being the president of the Saskatchewan Grain Growers Association

The Saskatchewan Grain Growers' Association (SGGA) was a farmer's association that was active in Saskatchewan, Canada in the early 20th century.

It was a successor to the Territorial Grain Growers' Association, and was formed in 1906 after Saskatch ...

and the Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company

The Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company (SCEC) was a farmer-owned enterprise that provided grain storage and handling services to farmers in Saskatchewan, Canada between 1911 and 1926, when its assets were purchased by the Saskatchewan Whea ...

. Maharg agreed to support the Martin government, although he stood for election as an independent member, not as a Liberal.[Lisa Dale-Burnett, "Maharg, John Archibald (1872-1944)", ''Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan''.]

/ref> By maintaining a close connection to the farmers with the support of Dunning and Maharg, the Martin government was re-elected in the 1921 provincial election with a substantial majority, although some Progressive candidates were also elected, forming the official opposition

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. This article uses the term ''government'' as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning ''th ...

. Martin kept Dunning as Provincial Treasurer, and appointed Maharg as Minister of Agriculture.[

] The situation changed with the federal election late in 1921. The federal Progressives continued to oppose the unpopular federal Liberals. Premier Martin intervened in the election at the local level in Saskatchewan, campaigning for Liberal candidates, including the Liberal candidate in Regina.

The situation changed with the federal election late in 1921. The federal Progressives continued to oppose the unpopular federal Liberals. Premier Martin intervened in the election at the local level in Saskatchewan, campaigning for Liberal candidates, including the Liberal candidate in Regina.[ His support for the federal Liberals angered the Saskatchewan Grain Growers Association, who began to discuss the possibility of establishing a separate farmer party.][ Maharg accused Martin of acting in bad faith, and resigned from Cabinet. He ]crossed the floor

Crossed may refer to:

* ''Crossed'' (comics), a 2008 comic book series by Garth Ennis

* ''Crossed'' (novel), a 2010 young adult novel by Ally Condie

* "Crossed" (''The Walking Dead''), an episode of the television series ''The Walking Dead''

S ...

and eventually became the leader of the opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

.[

The contretemps between Martin and Maharg had the potential to split the provincial Liberal party. A few months after the federal election, Martin resigned as premier and as leader of the Liberal party. The Liberals chose Dunning as the new party leader, and he then became premier of Saskatchewan.][ His immediate task as premier was to repair relations with the farm movement. He met with representatives of the Saskatchewan Grain Growers Association, to reassure them that he still supported the farm movement, rather than the Liberal government in Ottawa, and that the provincial Liberals were in fact a farmer party.][ He also requested copies of resolutions from the SGGA annual convention, presumably to assist in setting government policy.][ Dunning's overtures were successful, and the SSGA pulled back from suggestions that they should use their organisational strength to establish a separate farmer party.][

Dunning further established the position of the Liberal government in a series of by-elections, most of which resulted in Liberal candidates being elected. By the time of the next general election in 1925, Dunning had healed the rift with the farmers. The Liberals were re-elected with a substantial majority, and the Progressives were unable to build on their previous success in the 1922 election.][

The main issue the Dunning government faced was the falling price of wheat, which resulted from a post-war depression. His government supported the re-establishment of the ]Canadian Wheat Board

The Canadian Wheat Board (french: Commission canadienne du blé, links=no) was a marketing board for wheat and barley in Western Canada. Established by the Parliament of Canada on 5 July 1935, its operation was governed by the Canadian Wheat Bo ...

by the federal government.[ The Dunning government ended ]prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

after a 1924 plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, but sought to continue regulation through government-owned and operated liquor stores.

Dunning also supported efforts towards voluntary pooling of farm products, and the nascent

Dunning also supported efforts towards voluntary pooling of farm products, and the nascent Saskatchewan Wheat Pool

The Saskatchewan Wheat Pool was a grain handling, agri-food processing and marketing company based in Regina, Saskatchewan. The Pool created a network of marketing alliances in North America and internationally which made it the largest agricul ...

.[ His last major policy step as premier was to arrange for the enactment of legislation to authorise the sale of the Saskatchewan Cooperative Elevator Company to the ]Saskatchewan Wheat Pool

The Saskatchewan Wheat Pool was a grain handling, agri-food processing and marketing company based in Regina, Saskatchewan. The Pool created a network of marketing alliances in North America and internationally which made it the largest agricul ...

,[ over the objections of Maharg, who was still on the board of the SCEC. The Wheat Pool bought the SCEC for $11 million.][ (The equivalent in 2021 would be $166.91 million.) Farmers who bought shares in the SCEC for $7.50 in 1911 when Dunning was general manager would receive $155.84 per share in 1926.][

]

Federal politics: 1926 – 1930

Potential Liberal leader

Western farmers had traditionally been a source of support for the federal Liberals, but in the 1921 federal election many farmers had instead supported the Progressive party.

Western farmers had traditionally been a source of support for the federal Liberals, but in the 1921 federal election many farmers had instead supported the Progressive party.[ The new leader of the federal Liberals, ]William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Li ...

, had managed to defeat the Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

led by Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Arthur Meighen

Arthur Meighen (; June 16, 1874 – August 5, 1960) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the ninth prime minister of Canada from 1920 to 1921 and from June to September 1926. He led the Conservative Party from 1920 to 1926 and fro ...

, but only won a minority government

A minority government, minority cabinet, minority administration, or a minority parliament is a government and Cabinet (government), cabinet formed in a parliamentary system when a political party or Coalition government, coalition of parties do ...

. King was able to stay in power only by support from the Progressives. King was determined to rebuild the Liberals' farm support, particularly in western Canada.

In an effort to win back farmers, Mackenzie King began to court Dunning with his strong farm roots, encouraging him to enter federal politics. Campaigning in Saskatchewan at one point, with Dunning also on the speakers' platform, King spontaneously stated to the audience that he would like to see Dunning in the federal Cabinet. In 1926, Dunning accepted the invitation. Resigning as premier and leaving provincial politics, he was elected to the federal riding of Regina by acclamation in a by-election held in March, 1926, as a member of the federal Liberals.[Parliament of Canada ParlInfo: The Hon. Charles Avery Dunning, P.C.]

/ref>

Even though King brought Dunning to Ottawa, there was a risk for King, namely that Dunning could displace King as the leader of the Liberals. In the 1925 election, the Liberals had actually come in second in seats in the House of Commons, behind the Conservatives, and only held onto power through another minority government with Progressive support. King had also been personally defeated in his own riding in Ontario.[Hutchison, ''The Incredible Canadian'', pp. 101-102.] He was only able to re-enter the Commons when the Liberal member for Prince Albert, Saskatchewan

Prince Albert is the third-largest city in Saskatchewan, Canada, after Saskatoon and Regina. It is situated near the centre of the province on the banks of the North Saskatchewan River. The city is known as the "Gateway to the North" because ...

resigned his seat. King was elected in the Prince Albert by-election. King was able to stay in office as prime minister, but his position as party leader was not strong.

In light of the 1925 election results and King's personal defeat, some of the power brokers in the Liberal party began to consider whether Dunning would make a better leader than King. Quiet behind-the-scenes preparations started to be made, in case King stumbled badly and it was necessary to install Dunning as leader.[

By June, 1926, King was no longer able to govern. His minority government, elected only half a year earlier in the 1925 election, depended on support from the Progressives, but a political scandal in the Customs department triggered the withdrawal of Progressive support. Dunning, now in the House of Commons, vigorously defended the Liberal government, providing strong support for King, but knowing that King's defeat might well make him Liberal leader.][Hutchison, ''The Incredible Canadian'', pp. 116-117.] Facing a vote of censure in the Commons which, if passed, would likely bring down his government, on June 28, 1926, King requested that the Governor General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

, Viscount Byng of Vimy

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

, dissolve Parliament and call a general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

. Byng refused, relying on the reserve power

In a parliamentary or semi-presidential system of government, a reserve power, also known as discretionary power, is a power that may be exercised by the head of state without the approval of another branch or part of the government. Unlike in a ...

invested in him by the Imperial government. King immediately resigned, and Byng called on Meighen, now the Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

, to form a government.

The Liberals and Dunning were now in opposition. King's status as party leader was even more in doubt. The movement among leading Liberals to draft Dunning as a replacement as party leader grew stronger, now almost out in the open.[

However, the party standings in the House of Commons were so close that Meighen was unable to put together a stable government. Appointed as prime minister on June 28, 1926, Meighen lost a vote of confidence in the Commons by one vote only a few days later, at 2 a.m. on July 2, 1926. Meighen in turn requested that the Governor General dissolve Parliament. This time Byng granted the dissolution, with the ]general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

set for September.

King campaigned on the basis that Byng's refusal to grant him a dissolution, and then in turn granting a dissolution to his political opponent, was unwarranted Imperial interference in Canadian affairs. The controversy, known as the King-Byng Affair, was a winning platform for King and the Liberals. They were returned to power, although still with a minority government.

Doubts about King's status as party leader ended. Dunning was re-elected to his Regina seat by 900 votes and King again appointed him to Cabinet, no longer viewing him as a threat.

Minister of Railways and Canals: 1926 – 1929

When Dunning had been elected to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

in March 1926, King had immediately appointed him to the powerful position of Minister of Railways and Canals

The minister of transport (french: ministre des transports) is a minister of the Crown in the Canadian Cabinet. The minister is responsible for overseeing the federal government's transportation regulatory and development department, Transport Ca ...

in the federal Cabinet.[ King re-appointed him to the same portfolio after the Liberals were returned to office in September, 1926.][ The position was one of particular importance to western farmers, who were dependent on the national railway system to get their products to markets.

During his time as Minister of Railways and Canals, Dunning established himself as a friend of the Western farmer.][ Decisions made during Dunning's tenure included his accession to a petition from area farmers to have the Canadian National Railways build a branch line through his old home of Beaver Dale to ]Parkerview, Saskatchewan

Parkerview is an unincorporated area in the rural municipality of Garry No. 245, in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. Parkerview is located on Highway 617 at the junction of Township road 275 in eastern Saskatchewan.

See also

*List of com ...

. He also settled a longstanding debate by choosing Churchill, Manitoba

Churchill is a town in northern Manitoba, Canada, on the west shore of Hudson Bay, roughly from the Manitoba–Nunavut border. It is most famous for the many polar bears that move toward the shore from inland in the autumn, leading to the nickname ...

as the terminus of the Hudson Bay Railway.[ Upon completion of the railway and port facilities in 1931, Churchill became the closest Canadian port to ]Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

. The shipping route to Churchill was 1,600 kilometres shorter than the overland route to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

. Dunning was also a staunch supporter of Sir Henry Thornton, the U.S.-born Englishman who, in 1922 had taken over the presidency of the Canadian National Railways

The Canadian National Railway Company (french: Compagnie des chemins de fer nationaux du Canada) is a Canadian Class I railroad, Class I freight railway headquartered in Montreal, Quebec, which serves Canada and the Midwestern United States, M ...

.

Minister of Finance: 1929 – 1930

In 1929, when Dunning was still a relatively young man at age 44, King appointed him the federal Minister of Finance

A finance minister is an executive or cabinet position in charge of one or more of government finances, economic policy and financial regulation.

A finance minister's portfolio has a large variety of names around the world, such as "treasury", " ...

.[ As in his previous portfolio, Dunning earned a reputation for hard work and fairness. It was said that it was typical of Dunning that, although feeling ill, he remained on his feet throughout the reading and passage of his first set of ]estimates

{{otheruses, Estimate (disambiguation)

In the Westminster system of government, the ''Estimates'' are an outline of government spending for the following fiscal year presented by the cabinet to parliament. The Estimates are drawn up by bureaucrat ...

as Minister of Finance. As soon as the estimates were passed, Dunning collapsed and was rushed to the hospital to be treated for appendicitis.

Dunning was not only interested in domestic politics. He was also keenly interested in international politics, and particularly, in Canada's relationship with his "old country", the United Kingdom. Dunning participated in Canada's delegation to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

.

In 1930, when the United States proposed the draconian Smoot-Hawley tariff, Canada's response was the Dunning tariff with increased duties and further tariff preference for the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries

The Commonwealth of Nations is a voluntary association of 56 sovereign states. Most of them were British colonies or dependencies of those colonies.

No one government in the Commonwealth exercises power over the others, as is the case in a po ...

. The opposition Conservatives criticised the tariff on the basis that the imperial preference was prejudicial to Canadian interests.

Defeat in the 1930 election

Canadians went to the polls in the general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

of July, 1930, at the beginning of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. The Conservatives under their new leader, Richard Bennett, defeated King and the Liberals, winning a majority government. Although Bennett had opposed the Dunning tariff while in opposition, the Conservatives maintained the tariff, which stayed in effect until renegotiated in the late 1930s.

Dunning lost his Regina seat by over 3,500 votes (obtaining only two-thirds of the winner's total). Safe Liberal seats were offered to Dunning, but he turned them down, thinking that a business career would protect his family's financial future. He restarted his business career reorganizing an under-performing subsidiary of the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

, thereafter establishing a reputation as a brilliant re-organizer of insolvent companies.

Minister of Finance: 1935 – 1939

King and the Liberals regained power in the 1935 general election. Now firmly in control of the Liberal party and the government, he immediately went to Dunning, pressing him to re-enter politics.[ King convinced Dunning that he was needed in the tough economic times created by the Great Depression. A sitting Member of Parliament was persuaded to step aside, and Dunning was yet again acclaimed, in a 1936 by-election held in the constituency of Queen's in ]Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen Provinces and territories of Canada, provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has seve ...

. Dunning returned to the Finance portfolio. This time, one of Dunning's legacies was the establishment of the Central Mortgage Bank, the predecessor to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) (french: Société canadienne d'hypothèques et de logement) (SCHL) is Canada's national housing agency, and state-owned mortgage insurer. It was originally established after World War II, to help re ...

.

Dunning was still sometimes mentioned as a possible successor to King, but in 1938, Dunning suffered a heart attack.[ Unable to carry on the stress of his Cabinet position, and locked in a perpetual conflict with the other Saskatchewan minister in the Cabinet, Jimmy Gardiner, in 1939 Dunning retired from politics.

]

Second business career: 1940 – 1958

In ill health, Dunning relocated to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

. In 1940, he was appointed as president and CEO of Ogilvie Flour Mills Ogilvie is a surname of Scottish origin. It may also refer to:

People

*Ogilvie (name)

Places Australia

*Ogilvie, Western Australia

Canada

*Ogilvie, Nova Scotia

*Ogilvie Aerodrome, Yukon

*Ogilvie Mountains, a mountain range in Yukon

Scotland

* ...

, a position he held until 1947, when he was appointed chairman of the board. In addition to his duties with Ogilvie, Dunning continued his business of corporate reorganization. He sat on a number of prestigious corporate and bank boards, including that of the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

.[''Queen's Encyclopedia'': "Dunning, Charles Avery (1885-1958)".]

/ref>

During World War II, Dunning was chair of the National War Loans Committee, raising money for the war effort. He was also chair of Allied Supplies Limited, a company created by the federal government to co-ordinate the production of munitions and explosives.[

]

Chancellor of Queen's University at Kingston

In 1940, Dunning was awarded an honorary doctorate by Queen's University at Kingston

Queen's University at Kingston, commonly known as Queen's University or simply Queen's, is a public research university in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Queen's holds more than of land throughout Ontario and owns Herstmonceux Castle in East Suss ...

, and was appointed chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

of the university. Although Dunning was not himself a wealthy man, his contacts in the business world enabled him to raise considerable funds for Queen's. One story is that during a meeting a of the CPR Board, Dunning passed a note to Colonel Robert Samuel McLaughlin, a wealthy member of the Board, saying that Queen's needed a new engineering building. The note came back with an invitation to talk after the meeting. A new engineering building at Queen's was the result. Dunning also used his financial expertise for general fund-raising campaigns. With his knowledge of federal tax law, he was able to find a new way for companies to make donations and take considerable tax benefits, resulting in substantial donations to Queen's.[

Dunning's abilities earned him the gratitude of the university, which named Dunning Hall in his honour.][Queen's Encyclopedia: "Dunning Hall".]

/ref> The Chancellor Dunning Trust Lectureship was established by an anonymous donor, to "promote the understanding and appreciation of the supreme importance of the dignity, freedom, and responsibility of the individual person in human society". More recently, the university has established the Stauffer-Dunning Chair in Public Policy.

Death

Dunning died in 1958, aged 74, following kidney surgery. He is buried in Mount Royal Cemetery

Opened in 1852, Mount Royal Cemetery is a terraced cemetery on the north slope of Mount Royal in the borough of Outremont in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Temple Emanu-El Cemetery, a Reform Judaism burial ground, is within the Mount Royal grounds. Th ...

in Montreal.

Honours

In 1985, Dunning was designated as a National Historic Person by the federal government's heritage registry.

In 2005, as part of Saskatchewan's centennial celebration, Dunning's memory was commemorated in two ways. First, the Provincial Revenue Building was renamed Dunning Place,[ recognising Dunning's long tenure as Provincial Treasurer. The Saskatchewan Cooperative Elevator Company also had its offices in the building when Dunning was general manager.

Second, on the initiative of Saskatchewan's ]Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, Dr. Gordon Barnhart, Dunning's gravesite in Montreal's Mount Royal Cemetery was commemorated by a bronze plaque, recognizing Dunning's contribution to the people of Saskatchewan.

Dunning Hall at Queen's University is named after Dunning. Queen's School of Business occupied Dunning Hall for many years. Since 2002, it has housed the Department of Economics.

Dunning Hall at Queen's University is named after Dunning. Queen's School of Business occupied Dunning Hall for many years. Since 2002, it has housed the Department of Economics.[

In addition to his honorary degree from Queen's, Dunning also received honorary doctorates from ]McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter granted by King George IV,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill Universit ...

in 1939 and the University of Saskatchewan

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, t ...

in 1946.

Dunning Crescent in Regina is named after Dunning.City of Regina: Street Where You Live List.

/ref>

Electoral record

Summary

Dunning served the third-shortest term of the fifteen Premiers of Saskatchewan. As premier, Dunning won one majority government, in the general election of 1925. He served one continuous term, from April 5, 1922, to February 26, 1926,[Saskatchewan Archives: List of Saskatchewan Premiers.]

/ref> and was in office as premier for a total of .

Dunning was first elected as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan

The Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan is the legislative chamber of the Saskatchewan Legislature in the province of Saskatchewan, Canada. Bills passed by the assembly are given royal assent by the Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan, in the na ...

in 1916, and was re-elected in the general elections of 1917

Events

Below, the events of World War I have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 9 – WWI – Battle of Rafa: The last substantial Ottoman Army garrison on the Sinai Peninsula is captured by the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's ...

, 1921

Events

January

* January 2

** The Association football club Cruzeiro Esporte Clube, from Belo Horizonte, is founded as the multi-sports club Palestra Italia by Italian expatriates in First Brazilian Republic, Brazil.

** The Spanish lin ...

and 1925

Events January

* January 1

** The Syrian Federation is officially dissolved, the State of Aleppo and the State of Damascus having been replaced by the State of Syria.

* January 3 – Benito Mussolini makes a pivotal speech in the Italia ...

. He was acclaimed

An acclamation is a form of election that does not use a ballot. It derives from the ancient Roman word ''acclamatio'', a kind of ritual greeting and expression of approval towards imperial officials in certain social contexts.

Voting Voice vot ...

in the 1916 by-election, and again in the 1921 general election. Dunning won two contested constituency elections (in 1917 and 1925) by significant margins.[ His total time as a member of the Legislative Assembly from 1916 to 1926 was .

Dunning entered federal politics in 1926, being elected to the ]House of Commons of Canada

The House of Commons of Canada (french: Chambre des communes du Canada) is the lower house of the Parliament of Canada. Together with the Crown and the Senate of Canada, they comprise the bicameral legislature of Canada.

The House of Common ...

by acclamation in a by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

in March 1926.[ He was re-elected in the general election in the fall of 1926.][ He lost his seat in the general election of 1930, but was re-elected by acclamation in by-election in 1935, this time from the riding of Queen's in ]Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen Provinces and territories of Canada, provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has seve ...

. He served in the Commons for a total of 8 years, 6 months, 10 days.[

Dunning stood for election a total of nine times, provincial and federal. He was elected by acclamation five times, won contested elections three times, and was defeated once. His total time as an elected representative, provincial and federal, was 17 years, 200 days.

]

1925 General election

Dunning led the Liberal Party in one general election, in 1925, and won a majority government.

1 Premier when election was called; Premier after the election.

2 Co-Leader of the Opposition when the election was called; Co-Leader of the Opposition after the election.

Saskatchewan constituency elections

Dunning stood for election to the Legislative Assembly four times, once in a by-election and in three general elections, in two different ridings ( Kinistino and Moose Jaw County Moose Jaw County was a provincial electoral division for the Legislative Assembly of the province of Saskatchewan, Canada. The district was created as "Moose Jaw" before the 1st Saskatchewan general election in 1905. The riding was abolished int ...

). He was acclaimed twice, and won twice by substantial margins.[

]

1916 By-election: Kinistino

The by-election was called on the resignation of the sitting Liberal member, Edward Haywood Devline, to give Dunning, who had been appointed Provincial Treasurer, an opportunity to win a seat in the Legislation Assembly.

E Elected.

1917 General election: Moose Jaw County

E Elected.

X Incumbent.

1921 General election: Moose Jaw County

E Elected.

X Incumbent.

1925 General election: Moose Jaw County

E Elected.

X Incumbent.

Federal constituency elections, 1926 to 1935

After leaving provincial politics, Dunning stood for election to the House of Commons five times. He was elected to the House of Commons three times in one year, all from Regina, and defeated once. He later was elected from Queen's in Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen Provinces and territories of Canada, provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has seve ...

.[

]

1926 By-election: Regina

E Elected.

The by-election was called on the resignation of the sitting Liberal member, Francis Nicholson Darke

Francis Nicholson Darke (October 25, 1863 – July 17, 1940) was a leading citizen of Regina, Saskatchewan and served as Mayor of Regina, Member of Parliament and as a prominent businessman.

He was born near Charlottetown, Prince Edward Isl ...

, to create a vacancy for Dunning.

1926 General election: Regina

E Elected.

X Incumbent.

1926 By-election: Regina

E Elected.

X Incumbent.

The by-election was called on Dunning accepting a federal Cabinet position, an office of profit

An office of profit means a position that brings to the person holding it some financial gain, or advantage, or benefit. It may be an office or place of profit if it carries some remuneration, financial advantage, benefit etc.

It is a term used in ...

under the Crown, on October 5, 1926.

1930 General election: Regina

E Elected.

X Incumbent.

1935 By-election: Queen's, Prince Edward Island

E Elected.

The by-election was called on the appointment of the incumbent, James Larabee

J. James Larabee (10 April 1885 – 28 November 1954) was a Liberal party member of the House of Commons of Canada. He was born in Eldon, Prince Edward Island and became a merchant.

He was first elected to Parliament at the Queen's rid ...

, to an office of profit

An office of profit means a position that brings to the person holding it some financial gain, or advantage, or benefit. It may be an office or place of profit if it carries some remuneration, financial advantage, benefit etc.

It is a term used in ...

under the Crown, on December 18, 1935, to give Dunning, who had already been appointed Minister of Finance, the opportunity to re-enter the Commons.

References

External links

University of Regina Library – Saskatchewan Politics Research Guide: Charles Avery Dunning.Saskatchewan Government Booklet - Gravesites of Saskatchewan PremiersSaskatchewan Agricultural Hall of Fame

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dunning, Charles

1885 births

1958 deaths

Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada)

Premiers of Saskatchewan

Leaders of the Saskatchewan Liberal Party

Saskatchewan Liberal Party MLAs

Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada

Canadian Ministers of Finance

Canadian Ministers of Railways and Canals

Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Saskatchewan

Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Prince Edward Island

Liberal Party of Canada MPs

Chancellors of Queen's University at Kingston

Canadian farmers

British emigrants to Canada

Members of the United Church of Canada

People from Blaby District

Burials at Mount Royal Cemetery

The federal Liberals were increasingly unpopular in Saskatchewan, which contributed to the rise of the Progressives. The provincial Liberals continued to advance their position as a farmers' party, to the point that in 1921, Premier Martin severed the organizational ties between the Saskatchewan Liberal Party and the federal Liberal Party.Damian Coneghan, "Progressive Party", ''Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan''.

The federal Liberals were increasingly unpopular in Saskatchewan, which contributed to the rise of the Progressives. The provincial Liberals continued to advance their position as a farmers' party, to the point that in 1921, Premier Martin severed the organizational ties between the Saskatchewan Liberal Party and the federal Liberal Party.Damian Coneghan, "Progressive Party", ''Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan''. The situation changed with the federal election late in 1921. The federal Progressives continued to oppose the unpopular federal Liberals. Premier Martin intervened in the election at the local level in Saskatchewan, campaigning for Liberal candidates, including the Liberal candidate in Regina. His support for the federal Liberals angered the Saskatchewan Grain Growers Association, who began to discuss the possibility of establishing a separate farmer party. Maharg accused Martin of acting in bad faith, and resigned from Cabinet. He

The situation changed with the federal election late in 1921. The federal Progressives continued to oppose the unpopular federal Liberals. Premier Martin intervened in the election at the local level in Saskatchewan, campaigning for Liberal candidates, including the Liberal candidate in Regina. His support for the federal Liberals angered the Saskatchewan Grain Growers Association, who began to discuss the possibility of establishing a separate farmer party. Maharg accused Martin of acting in bad faith, and resigned from Cabinet. He  Dunning also supported efforts towards voluntary pooling of farm products, and the nascent

Dunning also supported efforts towards voluntary pooling of farm products, and the nascent  Western farmers had traditionally been a source of support for the federal Liberals, but in the 1921 federal election many farmers had instead supported the Progressive party. The new leader of the federal Liberals,

Western farmers had traditionally been a source of support for the federal Liberals, but in the 1921 federal election many farmers had instead supported the Progressive party. The new leader of the federal Liberals,  Dunning Hall at Queen's University is named after Dunning. Queen's School of Business occupied Dunning Hall for many years. Since 2002, it has housed the Department of Economics.

In addition to his honorary degree from Queen's, Dunning also received honorary doctorates from

Dunning Hall at Queen's University is named after Dunning. Queen's School of Business occupied Dunning Hall for many years. Since 2002, it has housed the Department of Economics.

In addition to his honorary degree from Queen's, Dunning also received honorary doctorates from